With groups come identification of groups, and with that come a class of objects termed graphical group identification device must be created. In the lands and countries of the J.-Pasaru, this device is called an ovecs /oʊ.vɛks/ (plural: ovexes /oʊ.vɛks.əs/, E.-Pasaru: žtlĭm /ʒt.lɨm/). This document describes what an ovecs is, how it is used, how one is made, and how it is different from an Earthling flag (and how similar the two can be sometimes).

An ovecs is a graphical group identification device that is primarily distinguished by the following parts, ordered by distinctiveness:

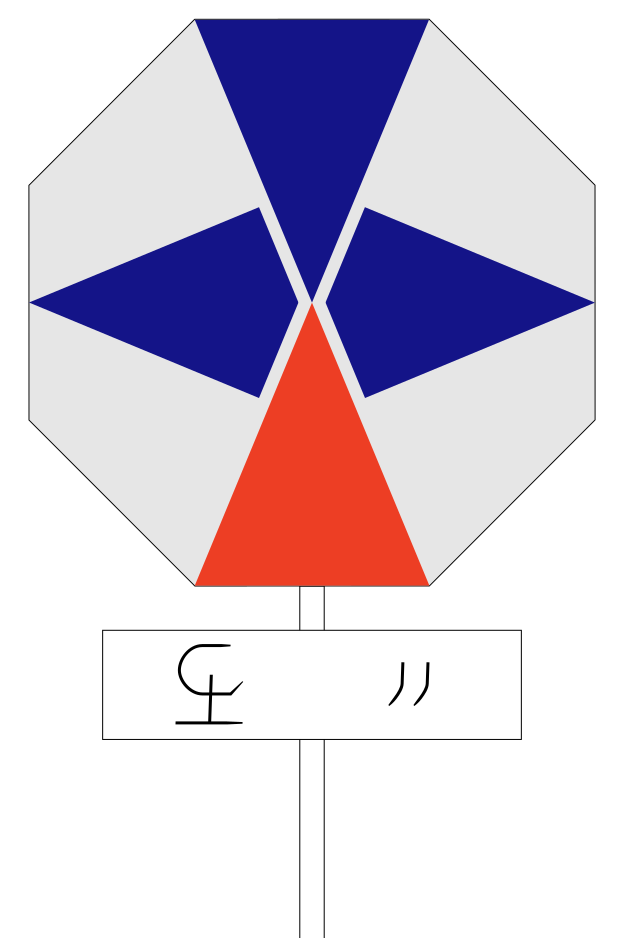

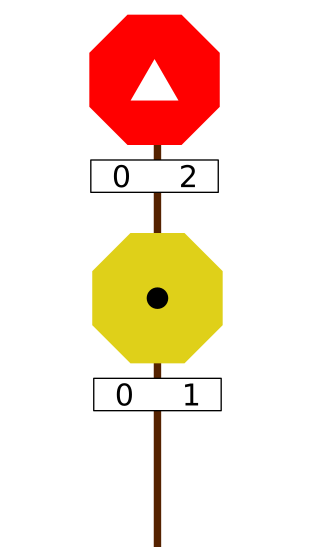

Three of those four items are indicated in the example ovecs as seen on the right. (There are actually real example ovexes as there are provisions to reserve some designs specifically for documentation purposes, but that’s for later.) But first, let’s go through each component in turn.

The banner is the most important part of an ovecs, so most would be forgiven for saying that it is the only part that matters. While it has many things in common with the face of an ordinary Earthling flag, it fulfils a slightly different corner of identification phase space.

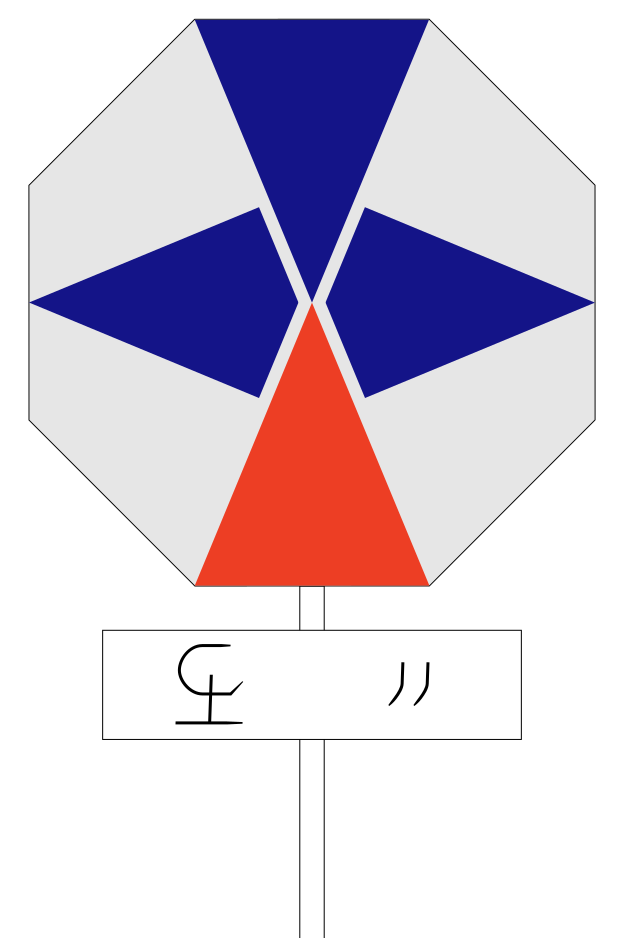

The banner is always an octagon with internal angles of 135°, and each corner and side has different names. A corner is called a pœ, and the edges are called naon.

| Symbol | Type | Short Name | Long name | Translation of the long name |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T | Corner | Troťnu | Üjbŕeu̲l | First legendary |

| Y | Yœn | Üjbŕeg̲i | Second legendary | |

| Ģ | Ģłyar | Pedu̲l | First lower | |

| P | Puunžol | Pedg̲i | Second lower | |

| L | Ltģra | Azu̲l | First upper | |

| Tx | Tyaontë | Azg̲i | Second upper | |

| I | Igléďs | Lëdænu̲l | First polar | |

| Px | Pešvo | Lëdæng̲i | Second polar | |

| B | Side | Blťu | Üjbŕeyaot | Legendary |

| Æ | Ænteħn | Pedu̲l | First lower | |

| LZ | LZaon·gerd | Pedg̲i | Second lower | |

| Pxx | Pllŭiwën | Cŕednu̲l | First central side | |

| N | Nbřurag | Cŕedng̲i | Second lower | |

| Ķ | Ķťülzéj | Azu̲l | First upper | |

| E | Eďdorae | Azg̲i | Second upper | |

| Š | Šbílsa | Lëdæn | Polar |

The long names are all descriptive – naonü̲jbŕeyaot is on the side of the legend, hence its name. The short names on the other hand are all named after units: the corners are the names of the Eight Leaders that have rescued the nation of Vohalyo from its near death in the year −40 PD, and the eight sides are named after their first eight descendants. Additionally, the central point also gets a name, cŕeďnzatť, and the names of the sides can also refer to the midpoints of those sides, if one explicitly prefixes either name with the word pœ.

So what does one do with the banner? Draw on it, of course.

Specifically, to make a flag there are three main parts: lines, colour and devices. Lines and colour complement each other, and devices sit atop of them.

Lines (E.-Pasaru: tšop, or pallo in informal contexts) cut up the banner’s surface into a finite number of regions. Although lines in most flags are straight, they are allowed to be curved, as long as areas cut up by the lines are all simply connected and there is an area δa > 0 that is less than all the areas of the region (the Rule of Non-Infinitesimals: no cutting up the name surface into any number of infinitely small areas.) The value of δa is sometimes set by flag manufacturers explicitly.

Lines are defined by their origin and destination points, which start off from the seventeen origin points defined for every flag (the eight corners, the eight midpoints and the centre). New points can be declared as the intersection of two lines, or from sliding an existing point along a previously defined line. Although curved lines are allowed, they are defined largely informally, usually by saying that they go across the point “in the wrong direction by some distance”.

Once all the lines are defined, the colours are placed in. They are usually only defined as basic colour terms: “red”, “green”, &c. They also obey a much looser version of the rule of tincture: “metals” now include such colours as sky and lime, and merely indicate that the colour is “high luminosity”. Additionally there are some colours that have medium luminosity, which can coëxist with both metals and colours (low intensity colours). Furthermore, because of the way the flags are created, gradients are possible in limited circumstances.

Then, on top of it, come the devices, which is just an arbitrary figure. They do not obey even the relaxed rule of tincture, and can be any shape, size and number, but still obey the Rule of Non-Infinitesimals. They all have one anchor point or two bonding points that is used to define the device’s position and orientation.

Below the banner is a rectangular board. The board has to be white, with a black border, and has black text. The text must have two or more characters in it, but it must not have an odd glyph length.

The origins of the legend is straightforward. Too many groups have the same banner design, so to differentiate a piece of paper with a short code was stuck on. Eventually this code was formalised and standardised, and the thing in general is accepted to become part of the flag. The Rule of Evens was created to ensure an æsthetical balance.

An ovecs can have more than one legend. This can happen for countries because it is officially bilingual, or writes in two different scripts in the same language. Otherwise, it might be because the group it represents has many names or that the combination of banner and first legend still has a collision. Legends closer to the banner are considered more important.

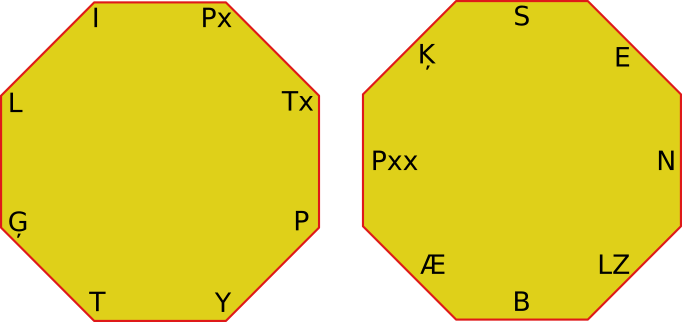

Between the legend or the plates are zero or more hexagonal plates, known simply as plates (E.-Pasaru: dulĭť). They are ciphers, in the sense that each one encodes a digit, though they historically encoded an entire integer. They are nonessential, which means that they can be discarded if space requires it.

The number that they encode is the flag’s succession index. When a country has a change in leadership, either by hereditary succession or by election, the flag is updated to reflect this change in leadership in a process named succession. This is done by simply incrementing the number written on the plate by 1.

Because of their nonessentiality, they are also largely unstandardised on an international level, which means that different vexillological unions, named pacts (AOďwāg), can have different digits. The picture indicated above – that of the Standard – is adapted as the international standards for any new pacts, but existing ones can continue to use their own set if need be. This is also a factor in explaining why the standard set has irregular behaviour for the digits 9 through 0 (12) – it was adapted as a combination of the most popular ones, and the combination just so happens to make sense in its historical content. Specifically, the figures are assigned by adding more to the previous one, but their position is based on defining a final symbol and working backward.

The existence of pacts also help in keeping the number small; this is done in two ways. First, unless there is only one country in a pact, there must always be a country in a pact that has the smallest succession index (either 0 or 1). If there is no such country, then 1 is subtracted from all members’ succession index until one of them hits the minimum. This is called snapback (nŕaoj) and happens automatically. The other more drastic measure is to simply declare unanimously that the successor index is to be reset to 0 at the beginning of some year for all members that did not receive an exemption.

Plates are useful in indicating the change in leadership of a particular country and are used extensively in historical maps where an increase in the succession index is a handy representation of change of leadership. However in the wild plates are much rarer and usually only appear in the homes or graves of current and former leaders of any type. They are, however, permitted to be attached to any flag provided that the correct succession index is used.

The frequency of snapback largely depends on the values of the pact: they might desire a large cardinal number to appear on their flags, in which they will be very rare if present at all; but other pacts, that prefer the exact opposite, might snapback a lot, to the point of it being a natural occurrence. However, no nation desires a very large number to show on the flag, if only for the simple reason that the reader of the flag will complain about having to process such a large number, or that too many digits would make the flagpole unnecessarily tall (a taller flag is harder to see from down below and is therefore considered less important than a shorter flag.) Nations deal with this in several ways:

The pole is a nonessential part of the flag, and in fact it is so nonessential that for the most part the public does not know about it. Nevertheless, it is still a topic worthy of a brief discussion.

For the most part, flags do not define pole colours, and they are usually left as the default colour of whatever material the pole is made of (e.g. brown wood or silver metal.) When they do, only three solid colours can be part of a pole, and if there’s more than one they must be striped. The directions of the stripes are usually horizontal or vertical, but can also be in any other direction if it is so warranted.

As mentioned earlier, the pole is not an essential part of the flag. Like the plate, it can be removed from a depiction of the flag without changing what it represents, but unlike the plate it does not have any special meaning that can be easily generalised to all flags. This makes them ignored even in places where plates would generally be included, explaining their general obscurity among the public.

All boards must be centred on the pole. Furthermore, they must have the same separation, usually ⁹⁄₁₄₄ of the height of the banners. The top of the pole must stay between the bottom and the top of the banner. but where exactly cannot be defined by the flag and can be wherever is convenient to the flag maker. They can be fastened in any inconspicuous way as well, although the majority are done by gluing a handle to the back that slots into the hole.

With a flag being created, all that is left is to put it up somewhere. The practise of putting up a flag is called mounting. There are several conventions for mounting flags, and those are, with minor variations, uniform across the world, by chance or by force.

Flags are mounted in a specific area, known as the field (senp̲arť). The field may be, but sometimes is not, clearly delimited, and may be defined in one or both of these two methods:-

Additionally, there is an additional area known as the field’s ring (nař ek senp̲arť) that can be any shape or size as long as it covers all of the field. The field’s ring is invented because the strict definition of the field makes it hard for architects to plan ahead for them.

There are norms with regards what should and should not be done in the field. For instance, one should not leave rubbish or other loose objects in it, and one should not run or unnecessarily disturb things inside it unless it is to remove rubbish or similar. Additionally, no object may be taller than the flag in the field, and there should be an open line of sight from the flag in some direction. though this is a loose, optional requirement and in any case the definition of an open line of sight is a very regional matter.

On the other hand, the field’s ring is much more lax and there are not many rules that are common to even a majority of all flag protocols. For the most part, they come in two flavours: the first is that they are just a random patch of grass, reserved for the expansion of the field but as of of yet still open for general use, or they can be extensions of the field and its rules to an arbitrary shape and size. The latter is often seen in places where the field is nearly or completely enclosed, like a “hole” in a building, and the former is seen almost everywhere else, though as always, exceptions exist.

The centre of a pole is the nominal location of the flag, that is, if someone asks for a millimetre-precise location of a flag, one points to the centre of its (primary) pole. It is therefore important to keep in track where poles are.

In general, the heights of all poles should be the same in the same field, although exception may be granted to exactly one pole, which can be shorter than all the others. That pole, which if present must be at some extreme position of the field, is the position of honour in which a particularly important flag may be placed, but which flag this might be is context-dependent and may not necessarily be the national flag. In any case, the poles must be at least six times taller than the size of all the banners, which are regulated for each flagpole such that each one has the same height. A popular industry standard is to have them be 533 cm tall – 1 ferā – and the special pole be ¹¹⁄₁₂ ferā tall.

The minimum separation of each pole must be at least half the length of the poles, but cannot exceed three-quarters that length. For a common layout, where all the poles are lined up straight, popular standards include ⅝, ⁷⁄₁₂ or ⅔ of the length of the pole. However, it is not necessary for flagpoles to be lined up like this. They can be in any configuration as desired, as long as the overall shape has some subjective level of symmetry or repetition or follow the contours of some natural feature. For those layouts, which for large fields can be very peculiar indeed, the separation rule is relaxed slightly, removing the minimum and trebling the maximum. Flags still cannot touch each other physically, however.

Finally, a completely unofficial but very common practise is to put a piece of hard ground in the area directly behind a flagpole. The reason is a practical one: a hard ground makes it easy for putting up and setting down a flag by allowing a steady platform for one to put a ladder or similar implement on. This is sometimes conspicuous and sometimes disguised, and there is a public perception that it is an important part of a flagpole, even though it isn’t.

Putting up and setting down a flag is a straightforward manner, and is usually not a very ceremonious one. There are two types, and it depends on whether or not the pole is a permanent installation or not.

The first type, mobile flags, can be short (three metres) and usually have pole markings. They are mounted simply by ramming the pole into the ground. These poles have a sharpened bottom so as to ease ramming, and fields that have holes for mobile flags are usually tapered at the bottom to accommodate this spike. Their shortness also indicates that they have prestige over the permanent flags, which is useful as guests are usually treated as such. Removing them is also simple; simply take the pole out of its original place.

Permanent flags and flagpoles are slightly different. Permanent poles are rarely coloured, and those that are are usually reserved for a single flag. They have holes drilled onto the back for the mounting brackets that are glued on every sign’s back. More recently sophisticated backs have been created with slots that can slide open and shut so that almost all heights can be accommodated.

With permanent poles one mounts a flag by bringing it over the top of the pole, then sliding it down to the desired height. Then, using either ordinary nails or special screws with twist knobs, the flag is screwed on, from bottom to top. This is why there are hard surfaces at the back of the pole; one would mount it by going that high up and fixing the flag in place. Dismounting the flag is trivial, then; simply mount the flag, but time-reversed.

Manymounting is the practise of mounting more than one flag on the same pole. It is different from merely putting one flag next to another in a field, and there are two, not just one, way to mount more than one flag on one pole. The most obvious way that this can be done is to simply put one flag on top of another. This is called serial manymounting (E.-Pasaru: želuue̲dulb̲lsa) One can repeat this for up to 6 flags at a time. The hard cap is to ensure that the highest flags are not so high that its details cannot be seen without using some kind of periscope or ladder. Still, the hard cap is rarely reached; the maximum that most will ever see is three, and two is far more common.

If for whatever reason more than six is needed, the typical solution is to mount the next set in another pole, slightly above and to the viewer’s right of the mounting point of the first pole with a beam angled to that effect. The tilted beam is to ensure that the situation is not to be confused with parallel manymounting. However, with each new extension beam one fewer flag can be mounted, leaving a new maximum of 21 flags; and of course all of those extra flags have to be supported somehow, usually using counterweights on the left-hand side or lots of trusses. Still, the new 21-flag limit is considered high enough for virtually all circumstances.

This kind of mounting is fairly simple and is used to indicate hierarchal relationships, such as city/state/country or individual/boss. It should be noted that the flags closer to the bottom are the ones that are considered more important, not the ones at the top; the reasoning here is that reading things is done starting at normal eye level and moving away from that, which in the case of flags, one starts at the one closest to eye level, which is the bottom flag. This also explains why the hard cap of six is not very restrictive; often one does not sign every hierarchical level on a flag, leaving only two or three important ones above one’s own.

Since flags are allowed to specify their own pole colours, what happens when two flags specify different colours are put together? There are several solutions: the most obvious one is to select one flag that dominates over the other, in which case we choose the bottom flag, as it is in the position of honour. But one can also elect to use the neutral colour, favouring no one, or paint different sections of the pole according to the flag just above it. Different societies have different solutions, and all three mentioned here are commonly understood.

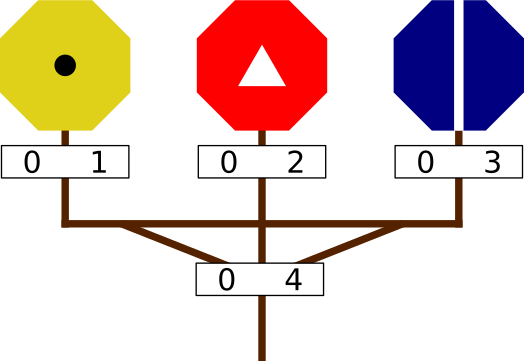

The other way to do it is to mount many flags, one next to each other, but on the same (modified) pole. This is called parallel manymounting (E.-Pasaru: želuue̲dulp̲llŭinbřu) and is much more complex than serial manymounting. In parallel mounting, the pole splits into two or more at some specified point, and from there on each one can can sport any flag or flag combination.

Parallel manymounting has several features that distinguishes it from its serial cousin. For instance, unlike serial manymounting there is no upper bound to the number of flags that can be parallel-manymounted in the same pole; one can choose to place as many flags in parallel on the same pole as one wishes, though of course limitations can occur by other means, such as available space.

These flags can be very large – extreme cases can have more than thirty or forty flags mounted on the same pole, so extra support is needed for these flag assemblies. All flags are fed through a truss (E.-Pasaru: aķdžœ) at the lower end of their individual poles, which then joins to the master pole (E.-Pasaru: lelëdæn), which is the pole that finally attaches the whole lot to the ground. In order to allow further support, diagonal rods known as struts (E.-Pasaru: unzl̲edæn) and vertical rods known as auxiliary poles can be used to reïnforce the structure. Struts do not touch the ground, whereas auxiliary poles do.

Secondly, flags mounted in parallel have equal standing with each other. This can be overridden by having one flag be shorter than all the rest, but this is rarely done and in the end the cultural norm is that when flags are mounted in parallel, no object referred to in that assembly is more important than another. If however one is required, one can mount a flag in series, but make the upper “flag” a parallel manymounting.

Finally, parallel mounting results in a consequence – there is a space for a legend to be placed at the base of the manymounting. This legend, which even if present is still just called a legend, is used to label the manymounting in its entirety, and usually draws its symbols from the name of the union of the objects that take part in the manymounting. This means that in some cases, unions don’t have flags of their own, just the parallel manymounting of its members.

Unlike Earthling (Western) flags, which are typically made out of coloured fabric, Ovexes are made out of hard, easily painted material such as wood or stone. Naturally, this means that paint is used to draw the picture in.

Those who make flags are called flagmen (yess̲en), unsurprisingly. As a group they make sure everything from forest to finish goes smoothly. They source the building material, cut it down to size, and draw the lines on the banner. We will now describe how the flag production process works.

It begins with the order to make a flag. All flags have a specification, a code in the cypher sense that specifies exactly where the lines are drawn and what the colours are, without actually drawing a diagram, which is at the time very space-consuming. It is through this medium that a flagman creates the flag. The code itself is made out of a list of shorthands and names, names for all of the points and most of the lines. More recently, a more public-facing version was created that replaces the code with a bunch of drawings, but this is only used in very formal contexts and not as the actual plan to make flags.

The flagman then scores the lines using a special set of rulers, both for lines and special curves, a couple of dividers, compasses, neusis rulers, and other geometrical implements. When all the lines are scored, (which include the lines that are thin bands in the final flag as well as lines that only act as helpers) the areas scored out are then painted, though not necessarily in the order the specification asks for. Next, if the flag calls for it, devices are attached to the specified anchor points, completing the banner.

The banner and any plates are partially prefabricated; the plates are completely so, but the banner’s prefab is just a white rectangle with a thin black border. The flagman has to write the banner’s characters in himself, but this can also be done using a prepared stencil.

Finally all the display parts have a bracket glued onto their backs, which are the part that allows them to be attached to any flagpoles. Interestingly, though flagmen make some poles, they are not responsible for all of them; architects and other home planners take care of all the static flagpoles, and the ones that the flagmen are responsible for are mobile.

With all the parts done, all that’s left is to assemble the flag. This is not done by the flagmen; all they do is to put all the flags into a box with a couple of nails and screws which they then ship off to the recipient. The screws are not conventional screws; as mentioned earlier they have a knob so they can be screwed or unscrewed without a screwdriver. The exact form of the screw used to be a trade secret, but nowadays is so strongly tied with flags no one ever uses them for anything other than flags. The whole box is then sealed, decorated and shipped off to the customer, which can be as humble as a single individual or it can be an entire country(’s government).

At first the flags are made out of wood and stone, and these are still how traditional flags are made today. However, in more recent times flagmen have experimented with more modern materials, such as aluminium and steel with retroreflective material.

With the change in material, change in production technique is required as well. By the year 19400 PDN, flags, especially when mass-produced, are computer-designed and also built by robots using plotters and other such flag-making devices. There’s a minor demand for hand-made flags, so flagmen are still in employment, but their numbers have never grown since their peak at 12500 PDN.

Flags are typically associated with countries, but that’s not the only thing they can do. They can, and often do, represent private entities such as companies, individuals, informal groups, events, ideas, groups of ideas, and even otherwise random assortments of unrelated objects. This is slightly different from the flags that Earthlings are used to because they are generally used only to represent a political subdivision, though of course they can and do get used to represent other things.

One usage case of the pole colour is to indicate the class of object that the flag represents. This is not standardised and is usually just an ad-hoc convention, but such conventions have been used and exploited over the years in different countries and different situations. For instance, in early 9th century Vohalyo, yellow poles generally indicate guilds and unions, green poles generally indicate the rural contingent, and red poles are for couriers and healthcare agents. “Official” (governmental) flags remain neutral in pole colour.

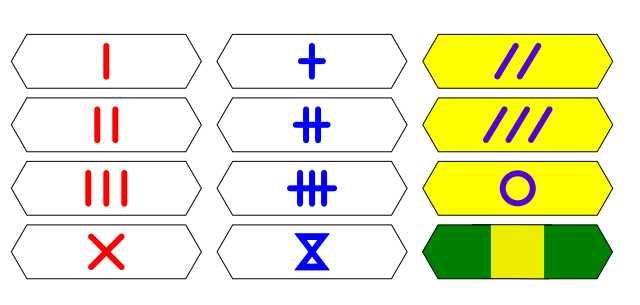

One surprising class of flags are flags that don’t represent anything at all, and are universally regulated to not represent anything at all. These are the documentation flags, which are a special class of extremely simple flags that are reserved for describing how they work in documents like this one. These flags are extremely simple, usually just a plain colour with a corresponding figure drawn inside, and the legend are two duodecimal digits. As a result, 144 flags can be used at a time, but there are actually about 800,000 of them. As a consequence, no legend in the wild can solely consist of digits.